“One runs the risk of weeping a little, if one lets oneself be tamed...”

― Antoine de Saint-Exupéry

Hello again, I hope you’ve all had a week that was kind to you. Here we are being treated to a few sunny days, a temporary lull in the forever damp, blandness that autumn has been. In one week—yes, I’ve been counting days—winter solstice will be passed. I, amongst many others I’m certain, will be rapturous to be passing the turning point in most the joyous annual event that is the shortest day! You can be sure there will be dancing, and singing… the wind can howl, metallic grey clouds can gallop across the hill, rain can fall harder than ever, I won’t care a hoot because minute by minute, each day, light will be returning.

So who of you will dance and sing with me at 04h27 next Friday?

Changing the subject entirely…

I read James Aldred’s A Goshawk Summer earlier this year, a beautifully written observation of diminishing, returning and flourishing natural life in The New Forest in the south of England. Written at a time when the forest was at its most peaceful for probably a thousand years - Lockdown 2020. As you can guess from the title, the book is predominantly concentrated on the Goshawk, more precisely, a pair of these very secretive raptors and the rearing of their young. All from a wonderful vantage point on a platform I high up in the canopies of trees.

Within the pages of his fascinating journal writing Mr Aldred records some of the daily goings on of several other of the forests inhabitants, curlew, traces of pine marten, which disappeared from the area over 100 years ago and the fox. It is from his notes on this last delightful woodland creature and a sad find here on my hill that I weave my story today… a true story of one of the lesser known habits of the fox, how it is not always kind or glorious but a sad fight for survival that the weakest do not win.

Fox tale and feather.

The light was fading fast on that evening early in May, I remember there were buttercups dancing in the meadows under a sinking sun, a barn owl calling from lower down the hill, its sound carried on a warm southerly breeze and with it the scent of cow parsley and honeysuckle. With my camera slung over my shoulder, I was returning from checking my three ewes, two of which had young lambs and the third about to give birth. All three were content, grazing in lush grass and meadow flowers on an evening that held all the promise of summer days yet to come. I decided to return to the house via the lane we had uncovered during confinement; the long way round because the evening was one for lingering in.

Lining the lane, after two years of finally having enough light for the plant life to reappear, on the woodland side were thousands of stitchwort, in the low light of the evening they shone like tiny earth stars. On the other, running along side the meadow, forget-me-not swayed in graceful abundance. As I was about to turn up the sharp slope Seth and I had painstakingly dug and rebuilt to enable us to climb more easily into the woods, something caught my eye. A light, like a gemstone, caught in the last of the sun, was glinting from amongst the tiny blue flowers. Curious, I stopped and parted the stems, halting again almost immediately.

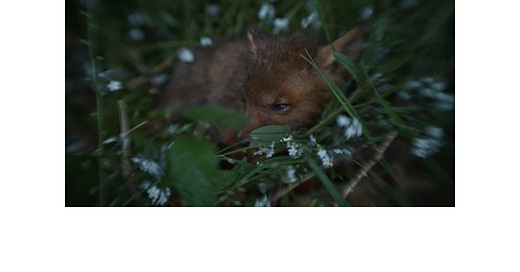

There, lying motionless but seeming perfectly comfortable in her bed of wild was a young fox cub. For just a few seconds I was startled—foxes are vicious creatures when they feel cornered even a young one like this—I searched quickly through the trees and over the fence to the meadow for her mother. In the gloaming I saw the black silhouette of owl gliding over the tree tops, its haunting call ceased but nothing more. The tiny fox just lay there, silently staring straight ahead through the tiny blue flowers.

It took me several more seconds to realise that not only was she not moving, she wasn’t breathing. It was the saddest and most curious find I’ve ever come across. There wasn’t a mark on her, no sign of having been hunted either by man or beast. This beautiful young creature, it appeared to me, had quite simply found a comfortable place to die and waited for her time to come.

The serenity of this peaceful scene made foolish tears burn behind my eyes. I ran up the slope to the house to find a spade and old sheet to use as a shroud. As beautiful as the sight was, I had to bury her. The scent of food, especially meat that is putrefying carries for miles and my chickens were not more than 50 metres away, I didn’t want to risk attracting other unwanted scavengers.

I buried her under a star filled indigo sky, in a small hazel copse by the river.

I still felt sad but my tears dried.

It is amazing how practicality can override emotion, even in times of sadness.

I walked back to the house in the blackness of the night, followed by the intermittent hoot of the barn owl, as if it was ensuring my safe home. When I finally stepped inside the door into a bright kitchen, William, berating me for wandering around in the dark alone, reached up to remove something from my hair, a single feather.

An owl feather.

I still didn’t understand—though I should have done, I’ve had to rear enough orphaned lambs through my life—why a young fox would just curl up and die. A few evenings later as I read a paragraph of A Goshawk Summer, lost in Mr Aldrid’s entrancing descriptions of three fox cubs playing in the warm morning sunlight, he continues to explain how a vixen will banish the weakest cub from the den if she senses difficulty in finding enough food to feed all. I did not know this of foxes. As I lay the book down, relinquishing words for sweet dreams, I realise this is exactly what had happened to the fox in the forget-me-not.

About James Aldred

Emmy award winning documentary cameraman, specialising in natural history and filming from ropes at height in any environment. Starting out as an assistant on Hollywood productions, James was then trained in-house by the BBC Natural History Unit, and has spent the last 20 years working regularly with the BBC, National Geographic and Discovery.

Here two of my favourite

reads of the week, there have been so many it’s hard to choose but Simon wrote this which quite literally made me stop and gasp while I was walking. His gentle voice, reading his own profoundly moving prose are exquisite.And I simply can’t resist sharing this with you, a most extraordinary and delicious melange of bacon, coffee and maple cooked into a jam by

who writes A Private Chef, to eat with your Christmas turkey.With love

Decisions made by Mothers in order to survive can seem cruel at times, yet necessary for the remaining members of her family to endure. I believe the owl was an Angel protecting the dear fox until a like minded Being of Light , like yourself, performed the final rite of its earthly body.

Have you heard the quote "When angels are near feathers appear"? It's a sign that they're near, offering their love, guidance and support. I believe you were chosen for your purity of spirit to lay to rest the wee fox, only to be done with the understanding of a Mother. What a precious moment for all! Love n Light dear Susie!

What a beautifully poignant story, Susie! I feel like Owl and Fox were interwoven that night and you were blessed with a feather of gratitude for your kindness with the cub. Having recently written about The Monarch archetype, I can't help but see that pattern with the vixen in your tale. She had to make a very difficult decision for the benefit of the group. She's a true queen, that one.