of moss and time…

In endless search of forgotten treasures… a promise.

“There is nothing like looking, if you want to find something. You certainly usually find something, if you look, but it is not always quite the something you were after.”

— J R R Tolkien

Hello lovely friends, readers and writers, how are you all? Especially all in the northern hemisphere, I do hope those fierce January storms left you all unscathed. Friday (12/01) an arctic wind was so bitterly mean here I had to turn back from my walk, my extremities burning as if dipped in hot coals. I never turn back! My chagrin calmed only when in flinging back the shutters the following Saturday and Sunday morning I was greeted by sunshine. Warmth, so very welcome, I do hope it reached you too.

This weekend the hill is devoured whole by thick fog - again! A bone chilling, cold dampness rolled up and over the hill from the East. I wrapped myself in wool and fleece, hoping for sunshine, to warm my back. I walk the entire south east quarter of the hill before 10 am, through a sheen of frosted fields, up to the highest Scots Pine, back down through the Silver Birch just as the sun climbs high enough to make their bark a shimmering vision of sheer loveliness.

A blissful start to Sunday.

Treasure Hunting - a passion ignited.

I grew up in Sussex, that is, now, West Sussex. I remember living in three separate houses, though I learned recently that in fact there were four. The third of those, I recall, was built on the outskirts of a village called Balcombe which momentarily claimed notoriety due to protests against fracking. A small cottage, backing onto fields which swept down to old Dutch barns and the farmyard. In all directions the fields were filled with a large flock of sheep bleating noisily either in search of their lost lambs or, more often, food.

To the left of the field directly behind our cottage was a small patch of woodland. As three young girls with over lively imaginations, we called it the Creepy Woods. This was largely due to an ancient yew tree, gnarled with age, roots departed from its grounding in earth, with spaces beneath large enough for small girls to wriggle into and scare themselves stupid with horror stories of trolls and goblins. Also, for reasons we didn’t understand at such tender ages, there were dead animals, squirrels, crows and magpies strung from the branches of the chestnut trees surrounding the yew. These were terrifying curiosities which sent us running in childish fear, screaming, as only little girls can, from the confines of dark woodland back into light and the comforts of the bleating flock.

Eventually, the Creepy Woods which became a completely irresistible place to be despite our fears, was the reason we fell upon—quite literally in our haste to leave one day—an old Victorian household dump. Hidden by brambles, thickets of spiny blackthorn and an old chestnut fence which we—with a small amount of force—were able to squeeze our skinny bodies through, was what appeared to our over enthusiastic child minds, an archeological paradise. From the day of its discovery we spent every hour possible through weekends and holidays balanced on the steep incline, armed with trowels and spades digging the soft, peaty soil away from possible treasures. Convinced that one of us would unearth something, anything that would be of historical interest, maybe something so rare and valuable it would be purchased by a museum. Placed in one of those fancy glass cases with details of where and when it was found, maybe even our names written underneath. We dreamed and dug and when the digging was fruitless we dug some more.

Over all the years we frequented that slope of broken bottles, plates and cups, rusty prams, bicycle wheels and earthenware marmalade jars, we found very little that was worth even taking home for cleaning. One whole Codswallop bottle our only true and coveted prize. My mother found an unexploded WW2 Mortar bomb, a treasure which held absolutely no value. However, it was a treasure that caused great excitement and a visit from a team of bomb disposal experts. They defused the bomb, immediately confiscated the remains and made a thorough search for others. There were none, but we were hesitant in returning after this, fearful of what we might find.

But curiosity won over fear eventually, we returned to our treasure hunting with renewed hope, even inviting a new neighbour to join us. A jolly red faced Irishman called Bert—though I’m not sure that was his real name, my mother said he had shifty eyes, we weren’t sure what that meant but by the sound of her voice it wasn’t a compliment—who thought us quite crazy in our beliefs but humoured our enthusiasm anyway. Within an hour of digging without much conviction, he unearthed a pottery vase. It looked like nothing at all, stained by soil and time but in one piece. He took it home, his reward for having spent time with three cheeky monkeys, he said.

We heard a little while afterwards he’d taken it to be valued by an expert at a prestigious auction house in London, sold it for many thousands of pounds. I don’t remember which Chinese dynasty it originated from but it was old. Very old and very rare. And very valuable. My mother wept for weeks at the injustice, muttering through her tears about the luck of the Irish. Something else we didn’t understand.

A passion inherited.

It is a rare year that Seth has no lessons on his birthday. He is delighted, of course he is, after all he is only fifteen, both grown up and still a child. Though the latter is left unmentioned it affirms that treasure hunting adventures are still very much still on the agenda. I am delighted! After finding two rusty and sadly irretrievable Mobylettes buried under two equally old and dilapidated cars earlier in the holidays, knowing how well I know the hill, its every track and woodland path, he hassles me relentlessly for ideas on where we might find other such treasures. After days of obsessional questioning, my patience beaten to a palpable mush, I promise a day of searching where ever he likes, so long as he halts his relentless questions.

He is excited when we leave after lunch, chattering constantly, convinced he will find that one item, abandoned to the ravages of time, half eaten by earth and its hidden inhabitants, something that he could show to friends once cleaned and restored; real treasure, like the moped—its called a Mobylette mum— retrieved from a friends cave which was subsequently given to him on the condition he repaired it and sent updates of progress. The Mobylette, dating from the sixties looked irreparable to me but over the following year, taking hours of research, joining Facebook groups, cleaning, replacing and repairing parts, he successfully started the engine and drove it off up the lane.

Proud/speechless mumma!

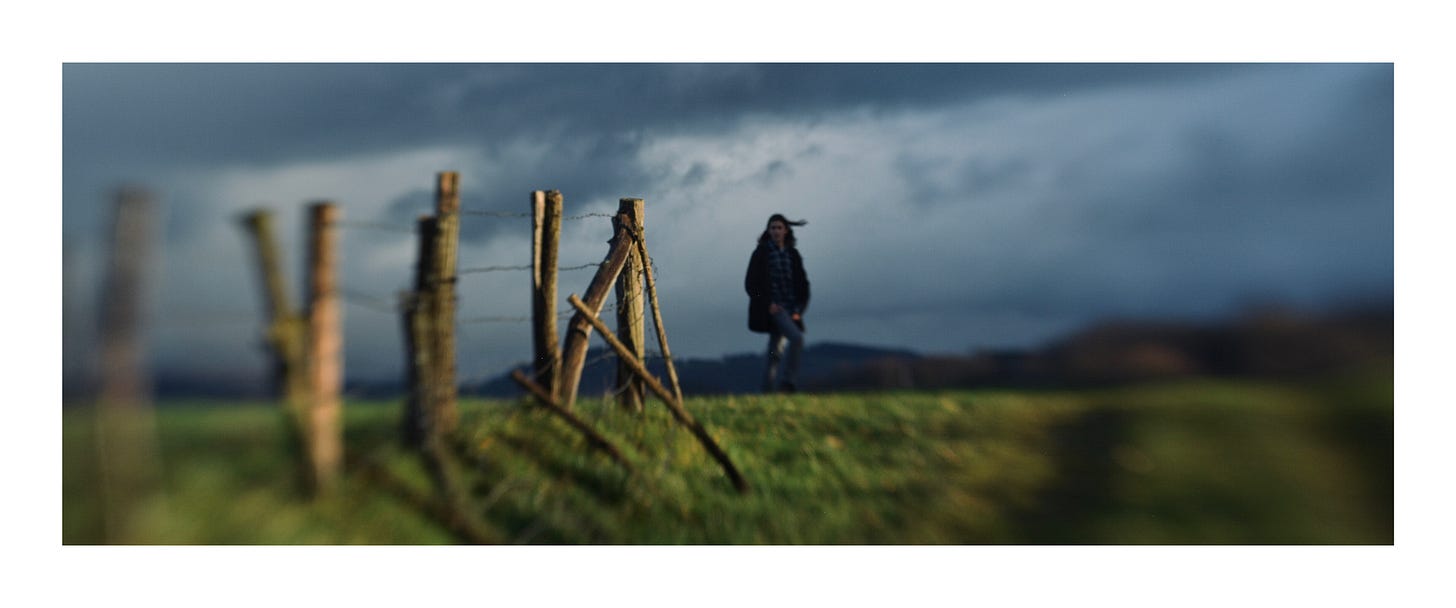

Armed with an ordinance survey map, snacks—to feed a 15 year old boys regular, as in every 30 mins, food requirements—and my camera, we set off towards the old mines, an area he is convinced will be filled with relics and priceless treasure. Indeed it is, though not the sort one can pop in a back pack and carry home. The whole area is scattered with rusting mining equipment, decayed and broken, half buried in moss and time. Great ropes of twisted steel, attached to pulleys crisscross the path, disappear into the river, occasionally revealing themselves again twisted within root systems on the opposite bank. And, of course, the mines themselves are still filled with the semi precious fluorine, if you have the machinery to extract it, which of course we don’t. We leave with a few glimmering pieces of quartz in our pockets as a reminder of the day only.

Undeterred we take a diversion. Glimmering dimly in my memory is a walk taken before his birth day, a vision of a tiny house buried deep in the scrubby oaks, hazel and briars suddenly materialising in a blur of recollection on a different hill. Seth waits for no further explanation, his excitement contagious as we head off, both of us almost running as constant heavy downpours do little to dampen high spirits!

Finding the track I’d taken more than fifteen years ago was not simple. These hills are a maze of ancient paths, some still trodden, others, most, overgrown and in many cases impassable. After an hour of climbing, peering between trees and through undergrowth, of detaching clothes caught on brambles, miraculously, we find the tiny abandoned shack I remember still standing. Still unloved. A vaguely decipherable small garden surrounds the building which then drops sharply down a steep slope. It reminds me immediately of the site of the Victorian dump I spent so many hours searching as a child. Here and there, caught in tangled bushes and fallen branches there are objects, deformed by age and nature but their rusty former uses still, just, discernable. Seth searches les alentours with audible glee and new hope, disappears, ecstatic, into the depths of decay. I don’t see him for another hour.

Curious as to why this house should have been built in such total isolation, I wander further up the slope in search of clues, another path, an old cart track, maybe even an old machine, anything to form an idea of the kind of life its long gone resident might have lead. Within minutes I spy another building almost entirely hidden by twisted and gnarled wilderness, years of nature inside and out. By the time Seth has exhausted his excavations, I have discovered two more.

Four tiny houses, built in the flimsiest of materials, within fifty metres, one from the other in the middle of woodland on the steep slope of a hill miles from anywhere.

Curiouser and curiouser…

We beat our way a little further into the wild, almost impenetrable undergrowth, stumbling at last, literally, onto a track. Impossible to tell from whence it came or where it went, perceivable only by yet more old buildings to each side. These were built in stone however, larger, with barns and cellars, walled gardens, though still very small. All were in ruins, giant lintels, keystones and linchpins, covered with moss and lichen, the remnants of beams lay haphazardly within fallen walls. Workers cottages; perhaps for the miners…

We have no chance to search further. Rain begins to fall again, heavy, persistent, the type of rain that soaks you in minutes. We chatter through the cacophony of the downpour clattering in trees, of torrents of water running down the slopes, oblivious of the long walk home ahead of us.

We are filled with questions without answers, both…

We reach the top of the hill breathing heavily, just as the sun, once again bursts through the clouds to shine, distant, on our own humble home.

We are quiet now, smiling at the intrigue of future discovery.

I hope he remembers I kept my promise…

I hope he remembers what his home looked like as the sun threw down late winter rays over our hill on the day of his fifteenth birthday.

“For deep time is measured in units that humble the human instant: millennia, epochs and aeons, instead of minutes, months and years. Deep time is kept by rock, ice, stalactites, seabed sediments and the drift of tectonic plates. Seen in deep time, things come alive that seemed inert.

― Robert Macfarlane,

If you like the idea of memoire journaling,

has worked on a beautifully put together 6 week course to guide you gently through the process, interested? Just tap the read more button below.

Susie, I love how you find the links between past and present--and how you describe both so lightly and with so much affection. I do hope Seth remembers this experience. I'm sure the joy he obviously felt will go a long way to cement it in his brain. Do you ever share your writing with him? That would help too. I'd love to know what he explored in the hour that you were discovering the four houses.

Thank you so much for sharing The Memory Mine. I've closed entry for this round but if anyone is interested, they can join the waitlist and I'll let them know as soon as it reopens.

A wonderful adventure. You gave Seth a marvelous memory for his birthday. And you can give it to him again in the form of a story.

Delightful, Susie!